The 2018 Lilly Awards

Monday, May 21st, 2018 at the Minetta Lane Theatre in New York City.

The show was hosted by Amanda Green, herself a Lilly board member. Presenters included Ira Glass, Sarah Ruhl, Mandy Greenfield, Celia Keenan-Bolger, David Cromer, and Cusi Cram. The Lilly Awards honored 16 award winners, including Monica Bill Barnes & Company, Jocelyn Bioh, Hannah Gadsby, and Carole Rothman. The Stacey Mindich ‘Go Write a Musical’ Award was given out for the first time, and, also for the first time, we had three Miss Lillys! The show featured performances from Monica Bill Barnes & Company, Georgia Stitt and Amanda Green, and Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Bobby Lopez.

Read Eve Ensler’s rousing speech at during this year’s award ceremony.

AWARD RECIPIENTS

Mixed Martial Arts Award

Monica Bill Barnes and Anna Bass

You’ve Changed the World Award

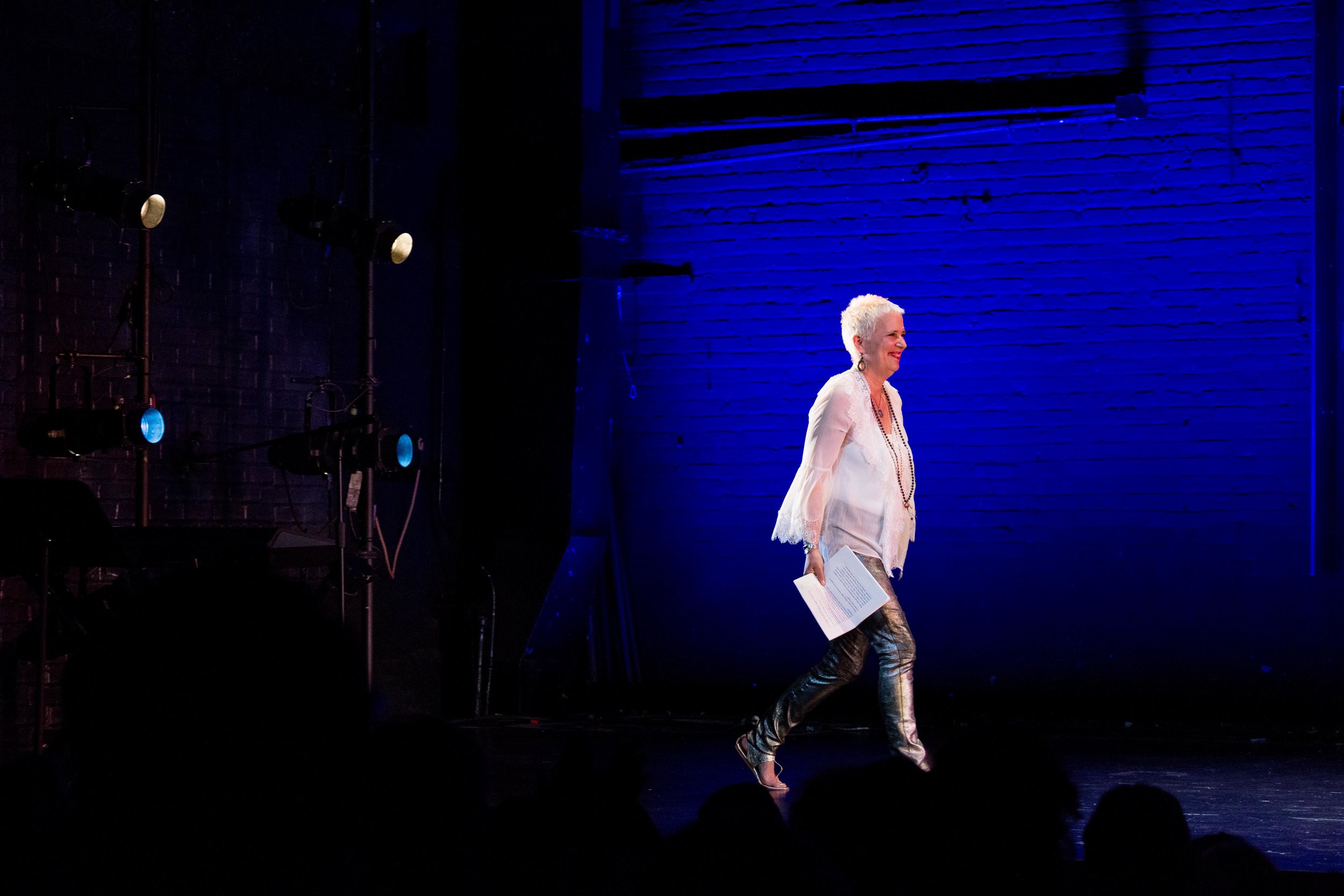

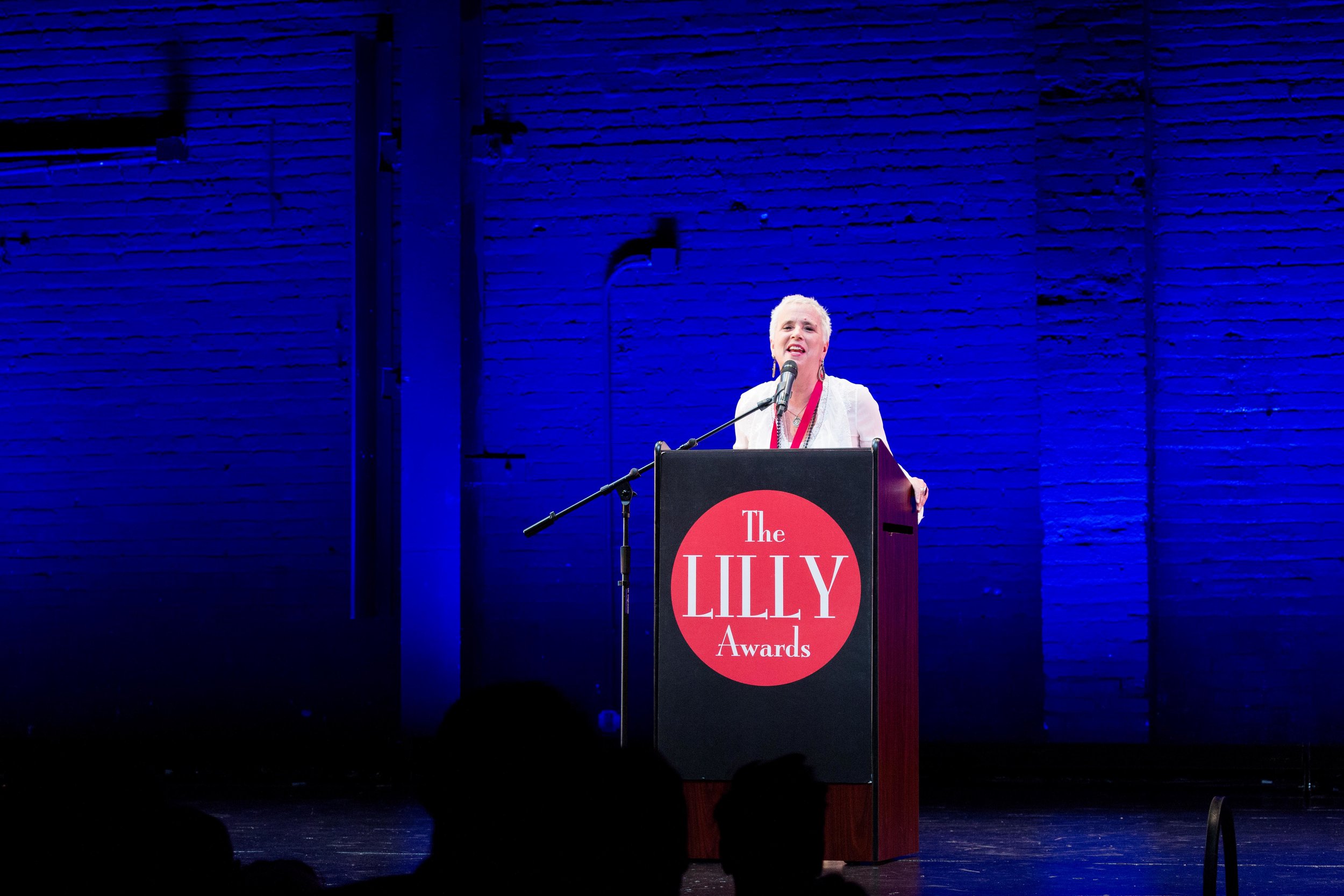

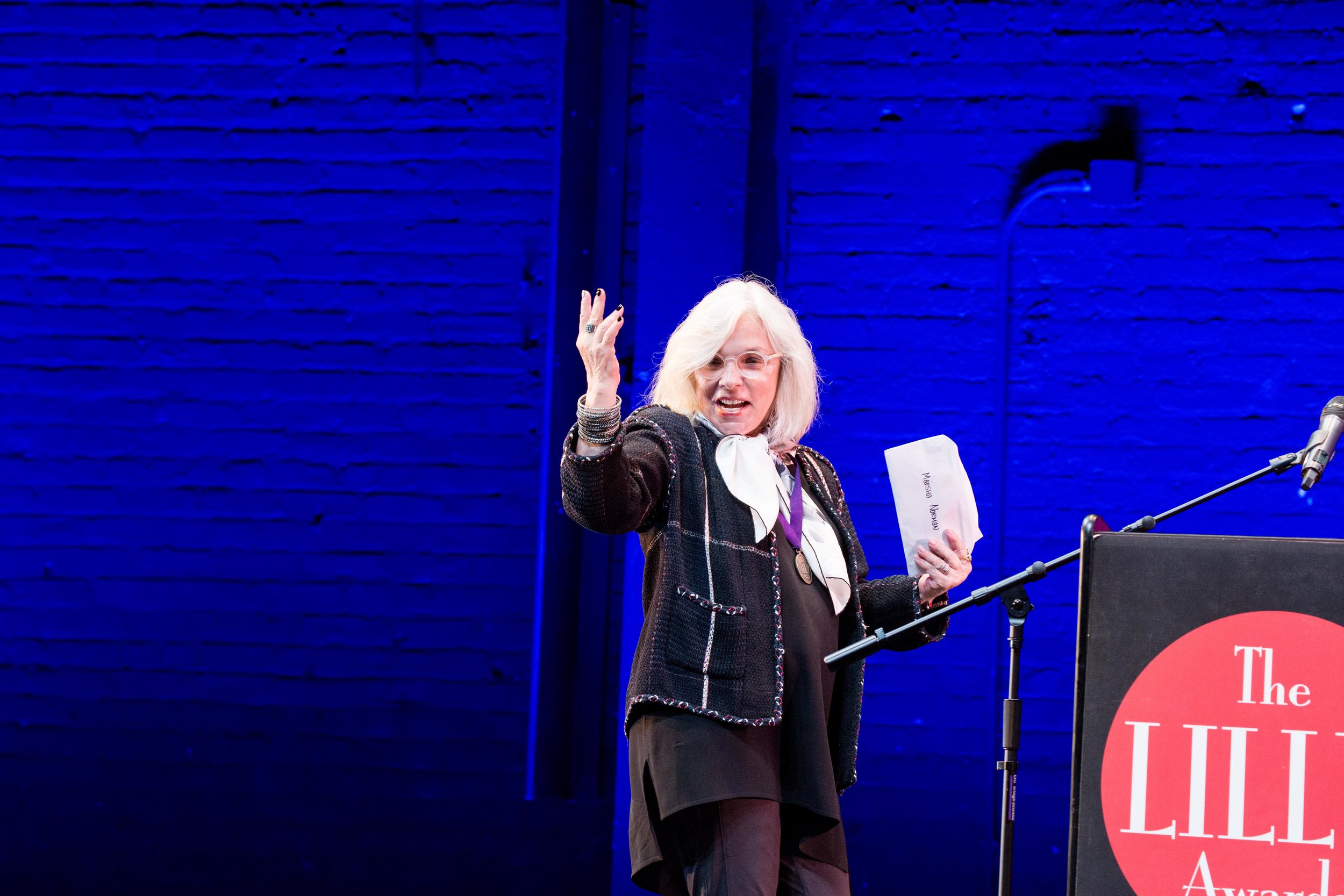

Eve Ensler

Daryl Roth Creative Spirit Award

Stacey Derosier

Fuck It, I’m Going to Say It Award

Lori Myers

Williamstown Theatre Festival ‘With The Females’ Award

Jocelyn Bioh

Mom of the Year Award

Kelda Roys

Producer of the Year Award

Carole Rothman

The New York Women’s Foundation Directing Apprenticeship Award

Abigail Jean-Baptiste

Stacey Mindich “Go Write a Play Award”

Jen Silverman

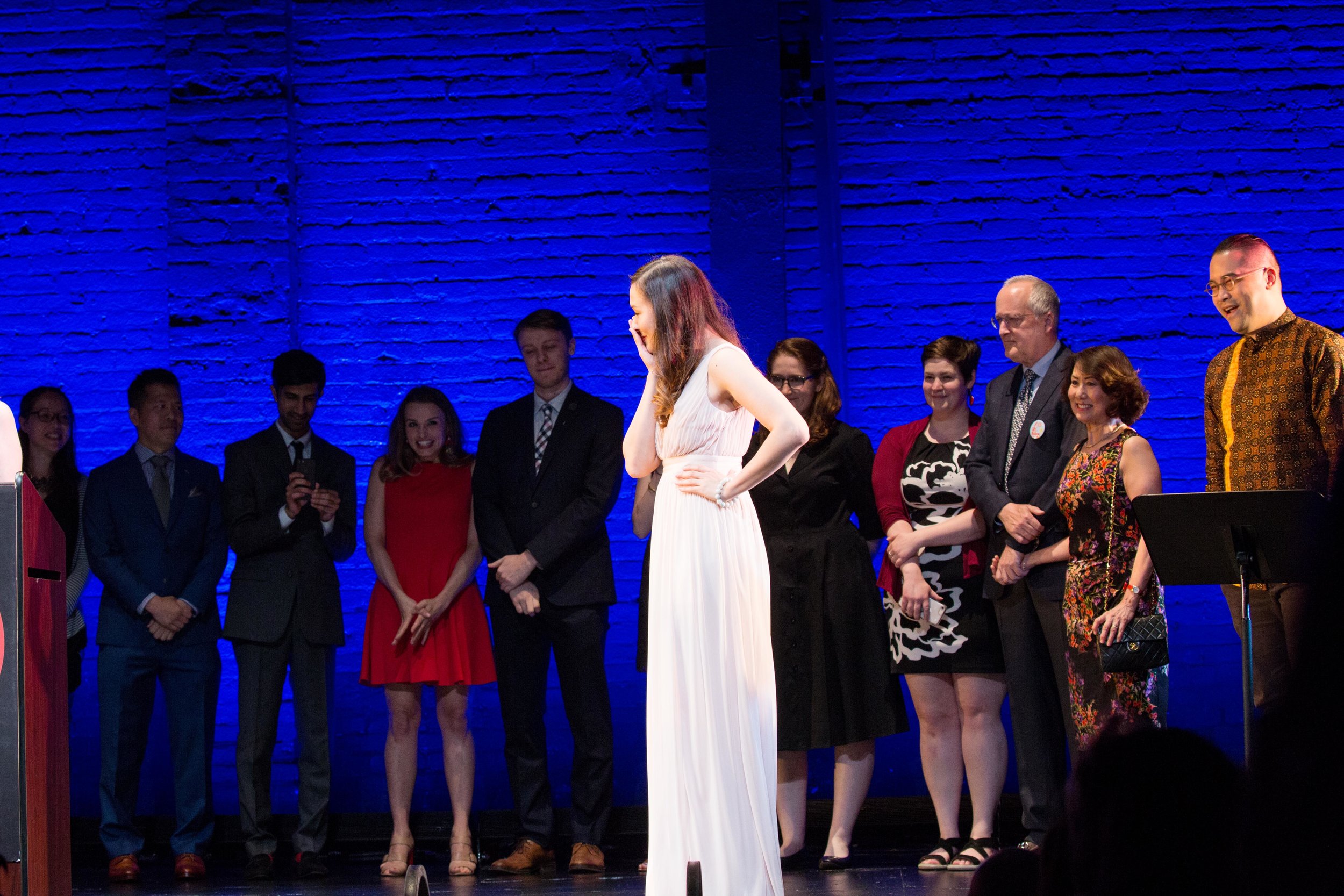

Stacey Mindich “Go Write a Musical Award”

Emily Gardner Xu Hall

Leah Ryan Prize

Gina Femia

Lilly Award

Hannah Gadsby

Photography by Emma Pratte

Portraits by Emma Pratte

Dear Young Women Playwrights

by Eve Ensler

On May 21, 2018, the You’ve Changed the World Award was given to Eve Ensler at the ninth annual Lilly Awards celebration. The complete text from her rousing speech is published here with Eve’s permission.

❝

Dear Young Women Playwrights,

This is a letter I have been meaning to write for some time and bless The Lilly Awards and the grand women who created them for inspiring me to do it now.

This letter is not meant to scare you but prepare you. I hope it will be a lot easier for you than it was for me and women of my generation, but racist patriarchy is a persistent and devious system of oppression. It is far more tenacious and relentless than I had imagined.

There are many things that will drive you mad as women playwrights.

Plays that get diminished by being called a woman’s play as if that’s an insult. We never call male driven plays, men’s plays. We call them plays. Because men are still seen as the drivers of the world. When I wrote The Vagina Monologues, journalists were constantly asking me with a kind of pity, how I felt that only women come to my show. I would say, “Only women? You mean 51% of the population? Thank you, women.”

I believe each artist, and particularly women artists, have a particular take and a unique way of organizing the world. Often, the conventional structure of plays is essentially patriarchal. Trying to squeeze our voice, our passion within that structure can undermine our voice and our imaginations. We need to trust the stories that come to us as well as the way we are compelled to tell the story.

If we write about social issues or feminism or racism or anything that matters we get called political and that is often meant disparagingly when, in fact, there is no such thing as a non-political play. If you write a play or musical that’s goal is to simply entertain, that is a political decision. And I adhere to what Adrienne Rich once wrote, “the moment a feeling enters the body is political.”

There is no reference point in the culture for a woman playwright who writes about the world and takes on the big issues. The big and important stuff has been consigned to men and if you trespass that boundary they will try to incinerate for your chutzpah and arrogance and border crossing. So, push yourself to write big, take up space.

Being a bisexual woman concerned with social justice, breaking taboos and telling the stories no one wants to talk about, writing emotionally and overtly passionately, writing monologues and moans, writing about pussies and death and homeless women and bellies and cancer and poop and Congo and war and AIDS and orgasms and sex trafficking and Freegans and mystical sexual divinity…well its been a hard road.

Even though your ambitions are equal to your male counterparts, you will discover that women are rarely given the serious and equal recognition we deserve. There are always modifiers or conditions. All the ways they will reduce you even as they celebrate you.

Consider this line from The New York Times, “The Vagina Monologues is probably the most important political play of the decade.” Note probably. Note political. Compliments or praise never feel whole or without reservation or erasure.

You will have to figure out how you remain totally vulnerable in order to create your plays while you construct protective armor. This is like learning how to open and close at the same time.

You will feel often that you are singing or spitting into a void and so you will have to develop your own spine, your own center. You will have to be what determines your own worth. You will fail at this probably more than you succeed, but if you have created a loving posse around you—and it is impossible to succeed without one—your posse will pick you off the floor and dust you off with the perfect combination of cherishing your gifts, reminding you why you are here, doing what you do, and with a tough love send you back out there.

You will want to quit and that is exactly what they want you to do, but your work here is much bigger than you. You are bringing stories, ideas, histories, images, characters, feelings of the marginalized, of the invisible and your fight is their fight and so you cannot quit.

You will have to survive both praise that has nothing to do with what you have written, and attacks that not only do not understand what you have written but have no desire or ability to understand. You will put your work before mostly white men who you probably wouldn’t invite for dinner and you will wait for them to determine the fate of a play you have worked on for years. And when they desecrate a work they have no capacity to understand, you will at first aim the dark feelings against yourself. But then, you will come to own your rage and use it as fuel. And even if they like your play and it becomes wildly successful, that will make you feel sick because they got to determine your existence yet again.

But you will see after awhile that critics are only a tiny part of the story. It is the audiences that matter. The people. Love and honor them more than the gatekeepers. The man who comes back three times to see your show because it is his healing. The women who break the silence on their own abuse for the first time as the curtain goes down. The young teenage girl who feels legitimized wearing her short skirt. They are the reason you write. Not for reviews, not for awards, not to be loved, not for fame or—certainly in the theater—not for money. The theater is the one place that still defies the virtual and allows people to connect in the present tense and feel and be transformed through a lived experience.

You will be told if you only wrote less difficult work or not so intense or not so emotional or not so in your face. They will call you names: man hating, strident, message mongering, polemical, didactic, pornographic, ax to grind, obscene, exhibitionist, hysterical. At first this will make you feel diminished, stupid, and unsophisticated but after a while, you will come to wear these names as a badge. Everything they throw at you will make you clearer, stronger, and more devoted about what you are doing and need to keep doing.

They will tell you your work isn’t commercial and that is code for, “isn’t written by a white man,” or “pure entertainment.” And to be honest, no one really has a bloody idea what will become commercial—meaning what play will attract a large audience. It has to do with timing, the political and cultural climate, and tapping into an invisible zeitgeist. I can’t tell you how many times I was told no one would come to see a play about vaginas, that it was professional suicide, that I would be marginalized and exiled.

We need to value our voices and the difference we bring. We need to stop trying to fit into their story and write our own. And we need to insist that the life of a playwright does not mean endless starvation and poverty and that subsidies for our work and getting paid well is critical to our survival.

You will come to know at 65 that this struggle, this pain, this rejection, this not giving up in the face of all odds, has been what in fact made you who you are. That you are as fragile as you are tough, vulnerable as you are fierce but, mainly, that you have lived your life, given yourself to a higher purpose. That surrender now fills you with a light, a strange confidence that is not arrogance but sureness, insane humor, extraordinary memories, and a body of work. Some great plays. Some that didn’t work as well. But you will love them all.

You will discover early on if you are writing about anything remotely controversial, you will have to do more than write a play. You will have to become a fundraiser and a marketer, a producer, an audience developer, maybe even the builder of a world movement. And as exhausting as this sounds, you will learn a lot and become more capable and able to help other women writing controversial plays.

The work of a woman playwright is not just to write your own play, but to upend this paradigm and bring in a new world. We need to create our own theaters, with women artistic directors, with female critics who think out of the box. We need to support each other and know that when one of us succeeds, it opens the door for many.

Writing for the theater—as woman, as a woman of color, as a trans woman—is a herculean task, but there is nothing like the theater: holy, sexy, transcendent.

You will be fed endlessly by the rehearsal process, watching your words come alive in the voice and bodies of amazing actors and directors. Love rehearsals as much as the finished show. That is where your craft is born. You will be fed by audiences who laugh and cry and are visibly shaken and transformed by your work. You will doing the sacred work, the work of poetry and the body and drama and passion and making the real visible and the invisible palatable. There is an ecstasy, a rapture that nothing in the world but the theater can bring. The dance in the dark between your words, your creation and willing strangers taking a journey to another place, another idea, another radiant shore.

So build your posse of tough loved ones, write and write and write and try to push boundaries and say what no one has said before. Say it in a way that only you can say it. Write about what matters to you and not about what you think will sell. Stop worrying about them—the mythical them who will celebrate you or crucify you—and simply work, work, work to tell the truth even if it terrifies you. Be the best playwright you can be. I wouldn’t trade one moment of my life in the theater. And I wouldn’t want to be anyone or anywhere else.

❞

Eve Ensler is the Tony Award winning playwright, activist, performer and author of the theatrical phenomenon and Obie Award winning, The Vagina Monologues. Some of Ms. Ensler’s plays include, Extraordinary Measures, Necessary Targets, OPC, The Good Body, Emotional Creature, In the Body of the World, and Fruit Trilogy. Ms. Ensler is the founder of V-Day and One Billion Rising.